Bayes Theorem

In this section we concentrate on the more complex conditional probability problems we began looking at in the last section.Example 19

Suppose a certain disease has an incidence rate of 0.1% (that is, it afflicts 0.1% of the population). A test has been devised to detect this disease. The test does not produce false negatives (that is, anyone who has the disease will test positive for it), but the false positive rate is 5% (that is, about 5% of people who take the test will test positive, even though they do not have the disease). Suppose a randomly selected person takes the test and tests positive. What is the probability that this person actually has the disease? There are two ways to approach the solution to this problem. One involves an important result in probability theory called Bayes' theorem. We will discuss this theorem a bit later, but for now we will use an alternative and, we hope, much more intuitive approach. Let's break down the information in the problem piece by piece. Suppose a certain disease has an incidence rate of 0.1% (that is, it afflicts 0.1% of the population). The percentage 0.1% can be converted to a decimal number by moving the decimal place two places to the left, to get 0.001. In turn, 0.001 can be rewritten as a fraction: 1/1000. This tells us that about 1 in every 1000 people has the disease. (If we wanted we could write P(disease)=0.001.) A test has been devised to detect this disease. The test does not produce false negatives (that is, anyone who has the disease will test positive for it). This part is fairly straightforward: everyone who has the disease will test positive, or alternatively everyone who tests negative does not have the disease. (We could also say P(positive | disease)=1.) The false positive rate is 5% (that is, about 5% of people who take the test will test positive, even though they do not have the disease). This is even more straightforward. Another way of looking at it is that of every 100 people who are tested and do not have the disease, 5 will test positive even though they do not have the disease. (We could also say that P(positive | no disease)=0.05.) Suppose a randomly selected person takes the test and tests positive. What is the probability that this person actually has the disease? Here we want to compute P(disease|positive). We already know that P(positive|disease)=1, but remember that conditional probabilities are not equal if the conditions are switched. Rather than thinking in terms of all these probabilities we have developed, let's create a hypothetical situation and apply the facts as set out above. First, suppose we randomly select 1000 people and administer the test. How many do we expect to have the disease? Since about 1/1000 of all people are afflicted with the disease, 1/1000 of 1000 people is 1. (Now you know why we chose 1000.) Only 1 of 1000 test subjects actually has the disease; the other 999 do not. We also know that 5% of all people who do not have the disease will test positive. There are 999 disease-free people, so we would expect (0.05)(999)=49.95 (so, about 50) people to test positive who do not have the disease. Now back to the original question, computing P(disease|positive). There are 51 people who test positive in our example (the one unfortunate person who actually has the disease, plus the 50 people who tested positive but don't). Only one of these people has the disease, so P(disease | positive) or less than 2%. Does this surprise you? This means that of all people who test positive, over 98% do not have the disease. The answer we got was slightly approximate, since we rounded 49.95 to 50. We could redo the problem with 100,000 test subjects, 100 of whom would have the disease and (0.05)(99,900)=4995 test positive but do not have the disease, so the exact probability of having the disease if you test positive is P(disease | positive) which is pretty much the same answer. But back to the surprising result. Of all people who test positive, over 98% do not have the disease. If your guess for the probability a person who tests positive has the disease was wildly different from the right answer (2%), don't feel bad. The exact same problem was posed to doctors and medical students at the Harvard Medical School 25 years ago and the results revealed in a 1978 New England Journal of Medicine article. Only about 18% of the participants got the right answer. Most of the rest thought the answer was closer to 95% (perhaps they were misled by the false positive rate of 5%). So at least you should feel a little better that a bunch of doctors didn't get the right answer either (assuming you thought the answer was much higher). But the significance of this finding and similar results from other studies in the intervening years lies not in making math students feel better but in the possibly catastrophic consequences it might have for patient care. If a doctor thinks the chances that a positive test result nearly guarantees that a patient has a disease, they might begin an unnecessary and possibly harmful treatment regimen on a healthy patient. Or worse, as in the early days of the AIDS crisis when being HIV-positive was often equated with a death sentence, the patient might take a drastic action and commit suicide. As we have seen in this hypothetical example, the most responsible course of action for treating a patient who tests positive would be to counsel the patient that they most likely do not have the disease and to order further, more reliable, tests to verify the diagnosis. One of the reasons that the doctors and medical students in the study did so poorly is that such problems, when presented in the types of statistics courses that medical students often take, are solved by use of Bayes' theorem, which is stated as follows:

Bayes’ Theorem

In our earlier example, this translates to

Plugging in the numbers gives

which is exactly the same answer as our original solution.

The problem is that you (or the typical medical student, or even the typical math professor) are much more likely to be able to remember the original solution than to remember Bayes' theorem. Psychologists, such as Gerd Gigerenzer, author of Calculated Risks: How to Know When Numbers Deceive You, have advocated that the method involved in the original solution (which Gigerenzer calls the method of "natural frequencies") be employed in place of Bayes' Theorem. Gigerenzer performed a study and found that those educated in the natural frequency method were able to recall it far longer than those who were taught Bayes' theorem. When one considers the possible life-and-death consequences associated with such calculations it seems wise to heed his advice.

Example 20

A certain disease has an incidence rate of 2%. If the false negative rate is 10% and the false positive rate is 1%, compute the probability that a person who tests positive actually has the disease. Imagine 10,000 people who are tested. Of these 10,000, 200 will have the disease; 10% of them, or 20, will test negative and the remaining 180 will test positive. Of the 9800 who do not have the disease, 98 will test positive. So of the 278 total people who test positive, 180 will have the disease. Thus so about 65% of the people who test positive will have the disease. Using Bayes theorem directly would give the same result:Try it Now 5

A certain disease has an incidence rate of 0.5%. If there are no false negatives and if the false positive rate is 3%, compute the probability that a person who tests positive actually has the disease.Counting

Counting? You already know how to count or you wouldn't be taking a college-level math class, right? Well yes, but what we'll really be investigating here are ways of counting efficiently. When we get to the probability situations a bit later in this chapter we will need to count some very large numbers, like the number of possible winning lottery tickets. One way to do this would be to write down every possible set of numbers that might show up on a lottery ticket, but believe me: you don't want to do this.Basic Counting

We will start, however, with some more reasonable sorts of counting problems in order to develop the ideas that we will soon need.Example 21

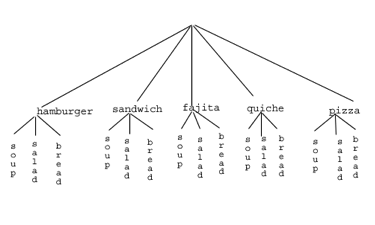

Suppose at a particular restaurant you have three choices for an appetizer (soup, salad or breadsticks) and five choices for a main course (hamburger, sandwich, quiche, fajita or pizza). If you are allowed to choose exactly one item from each category for your meal, how many different meal options do you have? Solution 1: One way to solve this problem would be to systematically list each possible meal: soup + hamburger soup + sandwich soup + quiche soup + fajita soup + pizza salad + hamburger salad + sandwich salad + quiche salad + fajita salad + pizza breadsticks + hamburger breadsticks + sandwich breadsticks + quiche breadsticks + fajita breadsticks + pizza Assuming that we did this systematically and that we neither missed any possibilities nor listed any possibility more than once, the answer would be 15. Thus you could go to the restaurant 15 nights in a row and have a different meal each night. Solution 2: Another way to solve this problem would be to list all the possibilities in a table:| hamburger | sandwich | quiche | fajita | pizza | |

| soup | soup+burger | ||||

| salad | salad+burger | ||||

| bread | etc |

This is called a "tree" diagram because at each stage we branch out, like the branches on a tree. In this case, we first drew five branches (one for each main course) and then for each of those branches we drew three more branches (one for each appetizer). We count the number of branches at the final level and get (surprise, surprise!) 15.

If we wanted, we could instead draw three branches at the first stage for the three appetizers and then five branches (one for each main course) branching out of each of those three branches.

OK, so now we know how to count possibilities using tables and tree diagrams. These methods will continue to be useful in certain cases, but imagine a game where you have two decks of cards (with 52 cards in each deck) and you select one card from each deck. Would you really want to draw a table or tree diagram to determine the number of outcomes of this game?

Let's go back to the previous example that involved selecting a meal from three appetizers and five main courses, and look at the second solution that used a table. Notice that one way to count the number of possible meals is simply to number each of the appropriate cells in the table, as we have done above. But another way to count the number of cells in the table would be multiply the number of rows (3) by the number of columns (5) to get 15. Notice that we could have arrived at the same result without making a table at all by simply multiplying the number of choices for the appetizer (3) by the number of choices for the main course (5). We generalize this technique as the basic counting rule:

This is called a "tree" diagram because at each stage we branch out, like the branches on a tree. In this case, we first drew five branches (one for each main course) and then for each of those branches we drew three more branches (one for each appetizer). We count the number of branches at the final level and get (surprise, surprise!) 15.

If we wanted, we could instead draw three branches at the first stage for the three appetizers and then five branches (one for each main course) branching out of each of those three branches.

OK, so now we know how to count possibilities using tables and tree diagrams. These methods will continue to be useful in certain cases, but imagine a game where you have two decks of cards (with 52 cards in each deck) and you select one card from each deck. Would you really want to draw a table or tree diagram to determine the number of outcomes of this game?

Let's go back to the previous example that involved selecting a meal from three appetizers and five main courses, and look at the second solution that used a table. Notice that one way to count the number of possible meals is simply to number each of the appropriate cells in the table, as we have done above. But another way to count the number of cells in the table would be multiply the number of rows (3) by the number of columns (5) to get 15. Notice that we could have arrived at the same result without making a table at all by simply multiplying the number of choices for the appetizer (3) by the number of choices for the main course (5). We generalize this technique as the basic counting rule:

Basic Counting Rule

If we are asked to choose one item from each of two separate categories where there are m items in the first category and n items in the second category, then the total number of available choices is m · n.

This is sometimes called the multiplication rule for probabilities.

Example 22

There are 21 novels and 18 volumes of poetry on a reading list for a college English course. How many different ways can a student select one novel and one volume of poetry to read during the quarter? There are 21 choices from the first category and 18 for the second, so there are 21 · 18 = 378 possibilities. The Basic Counting Rule can be extended when there are more than two categories by applying it repeatedly, as we see in the next example.Example 23

Suppose at a particular restaurant you have three choices for an appetizer (soup, salad or breadsticks), five choices for a main course (hamburger, sandwich, quiche, fajita or pasta) and two choices for dessert (pie or ice cream). If you are allowed to choose exactly one item from each category for your meal, how many different meal options do you have? There are 3 choices for an appetizer, 5 for the main course and 2 for dessert, so there are 3 · 5 · 2 = 30 possibilities.Example 24

A quiz consists of 3 true-or-false questions. In how many ways can a student answer the quiz? There are 3 questions. Each question has 2 possible answers (true or false), so the quiz may be answered in 2 · 2 · 2 = 8 different ways. Recall that another way to write 2 · 2 · 2 is 23, which is much more compact.Try it Now 6

Suppose at a particular restaurant you have eight choices for an appetizer, eleven choices for a main course and five choices for dessert. If you are allowed to choose exactly one item from each category for your meal, how many different meal options do you have?Permutations

In this section we will develop an even faster way to solve some of the problems we have already learned to solve by other means. Let's start with a couple examples.Example 25

How many different ways can the letters of the word MATH be rearranged to form a four-letter code word? This problem is a bit different. Instead of choosing one item from each of several different categories, we are repeatedly choosing items from the same category (the category is: the letters of the word MATH) and each time we choose an item we do not replace it, so there is one fewer choice at the next stage: we have 4 choices for the first letter (say we choose A), then 3 choices for the second (M, T and H; say we choose H), then 2 choices for the next letter (M and T; say we choose M) and only one choice at the last stage (T). Thus there are 4 · 3 · 2 · 1 = 24 ways to spell a code worth with the letters MATH. In this example, we needed to calculate n · (n – 1) · (n – 2) ··· 3 · 2 · 1. This calculation shows up often in mathematics, and is called the factorial, and is notated n!

Factorial

n! = n · (n – 1) · (n – 2) ··· 3 · 2 · 1

Example 26

How many ways can five different door prizes be distributed among five people? There are 5 choices of prize for the first person, 4 choices for the second, and so on. The number of ways the prizes can be distributed will be 5! = 5 · 4 · 3 · 2 · 1 = 120 ways. Now we will consider some slightly different examples.Example 27

A charity benefit is attended by 25 people and three gift certificates are given away as door prizes: one gift certificate is in the amount of $100, the second is worth $25 and the third is worth $10. Assuming that no person receives more than one prize, how many different ways can the three gift certificates be awarded? Using the Basic Counting Rule, there are 25 choices for the person who receives the $100 certificate, 24 remaining choices for the $25 certificate and 23 choices for the $10 certificate, so there are 25 · 24 · 23 = 13,800 ways in which the prizes can be awarded.Example 28

Eight sprinters have made it to the Olympic finals in the 100-meter race. In how many different ways can the gold, silver and bronze medals be awarded? Using the Basic Counting Rule, there are 8 choices for the gold medal winner, 7 remaining choices for the silver, and 6 for the bronze, so there are 8 · 7 · 6 = 336 ways the three medals can be awarded to the 8 runners. Note that in these preceding examples, the gift certificates and the Olympic medals were awarded without replacement; that is, once we have chosen a winner of the first door prize or the gold medal, they are not eligible for the other prizes. Thus, at each succeeding stage of the solution there is one fewer choice (25, then 24, then 23 in the first example; 8, then 7, then 6 in the second). Contrast this with the situation of a multiple choice test, where there might be five possible answers — A, B, C, D or E — for each question on the test. Note also that the order of selection was important in each example: for the three door prizes, being chosen first means that you receive substantially more money; in the Olympics example, coming in first means that you get the gold medal instead of the silver or bronze. In each case, if we had chosen the same three people in a different order there might have been a different person who received the $100 prize, or a different goldmedalist. (Contrast this with the situation where we might draw three names out of a hat to each receive a $10 gift certificate; in this case the order of selection is not important since each of the three people receive the same prize. Situations where the order is not important will be discussed in the next section.) We can generalize the situation in the two examples above to any problem without replacement where the order of selection is important. If we are arranging in order r items out of n possibilities (instead of 3 out of 25 or 3 out of 8 as in the previous examples), the number of possible arrangements will be given by n · (n – 1) · (n – 2) ··· (n – r + 1) If you don't see why (n — r + 1) is the right number to use for the last factor, just think back to the first example in this section, where we calculated 25 · 24 · 23 to get 13,800. In this case n = 25 and r = 3, so n — r + 1 = 25 — 3 + 1 = 23, which is exactly the right number for the final factor. Now, why would we want to use this complicated formula when it's actually easier to use the Basic Counting Rule, as we did in the first two examples? Well, we won't actually use this formula all that often, we only developed it so that we could attach a special notation and a special definition to this situation where we are choosing r items out of n possibilities without replacement and where the order of selection is important. In this situation we write:

Permutations

nPr = n · (n – 1) · (n – 2) ··· (n – r + 1)

We say that there are nPr permutations of size r that may be selected from among n choices without replacement when order matters.

It turns out that we can express this result more simply using factorials.

In practicality, we usually use technology rather than factorials or repeated multiplication to compute permutations.

Example 29

I have nine paintings and have room to display only four of them at a time on my wall. How many different ways could I do this? Since we are choosing 4 paintings out of 9 without replacement where the order of selection is important there are 9P4 = 9 · 8 · 7 · 6 = 3,024 permutations.Example 30

How many ways can a four-person executive committee (president, vice-president, secretary, treasurer) be selected from a 16-member board of directors of a non-profit organization? We want to choose 4 people out of 16 without replacement and where the order of selection is important. So the answer is 16P4 = 16 · 15 · 14 · 13 = 43,680.Try it Now 7

How many 5 character passwords can be made using the letters A through Z a. if repeats are allowed b. if no repeats are allowedCombinations

In the previous section we considered the situation where we chose r items out of n possibilities without replacement and where the order of selection was important. We now consider a similar situation in which the order of selection is not important.Example 31

A charity benefit is attended by 25 people at which three $50 gift certificates are given away as door prizes. Assuming no person receives more than one prize, how many different ways can the gift certificates be awarded? Using the Basic Counting Rule, there are 25 choices for the first person, 24 remaining choices for the second person and 23 for the third, so there are 25 · 24 · 23 = 13,800 ways to choose three people. Suppose for a moment that Abe is chosen first, Bea second and Cindy third; this is one of the 13,800 possible outcomes. Another way to award the prizes would be to choose Abe first, Cindy second and Bea third; this is another of the 13,800 possible outcomes. But either way Abe, Bea and Cindy each get $50, so it doesn't really matter the order in which we select them. In how many different orders can Abe, Bea and Cindy be selected? It turns out there are 6: ABC ACB BAC BCA CAB CBA How can we be sure that we have counted them all? We are really just choosing 3 people out of 3, so there are 3 · 2 · 1 = 6 ways to do this; we didn't really need to list them all, we can just use permutations! So, out of the 13,800 ways to select 3 people out of 25, six of them involve Abe, Bea and Cindy. The same argument works for any other group of three people (say Abe, Bea and David or Frank, Gloria and Hildy) so each three-person group is counted six times. Thus the 13,800 figure is six times too big. The number of distinct three-person groups will be 13,800/6 = 2300. We can generalize the situation in this example above to any problem of choosing a collection of items without replacement where the order of selection is not important. If we are choosing r items out of n possibilities (instead of 3 out of 25 as in the previous examples), the number of possible choices will be given by , and we could use this formula for computation. However this situation arises so frequently that we attach a special notation and a special definition to this situation where we are choosing r items out of n possibilities without replacement where the order of selection is not important.

Combinations

We say that there are nCr combinations of size r that may be selected from among n choices without replacement where order doesn’t matter.

We can also write the combinations formula in terms of factorials: